For leader of Joint Commission, healthcare must lead the world on climate change

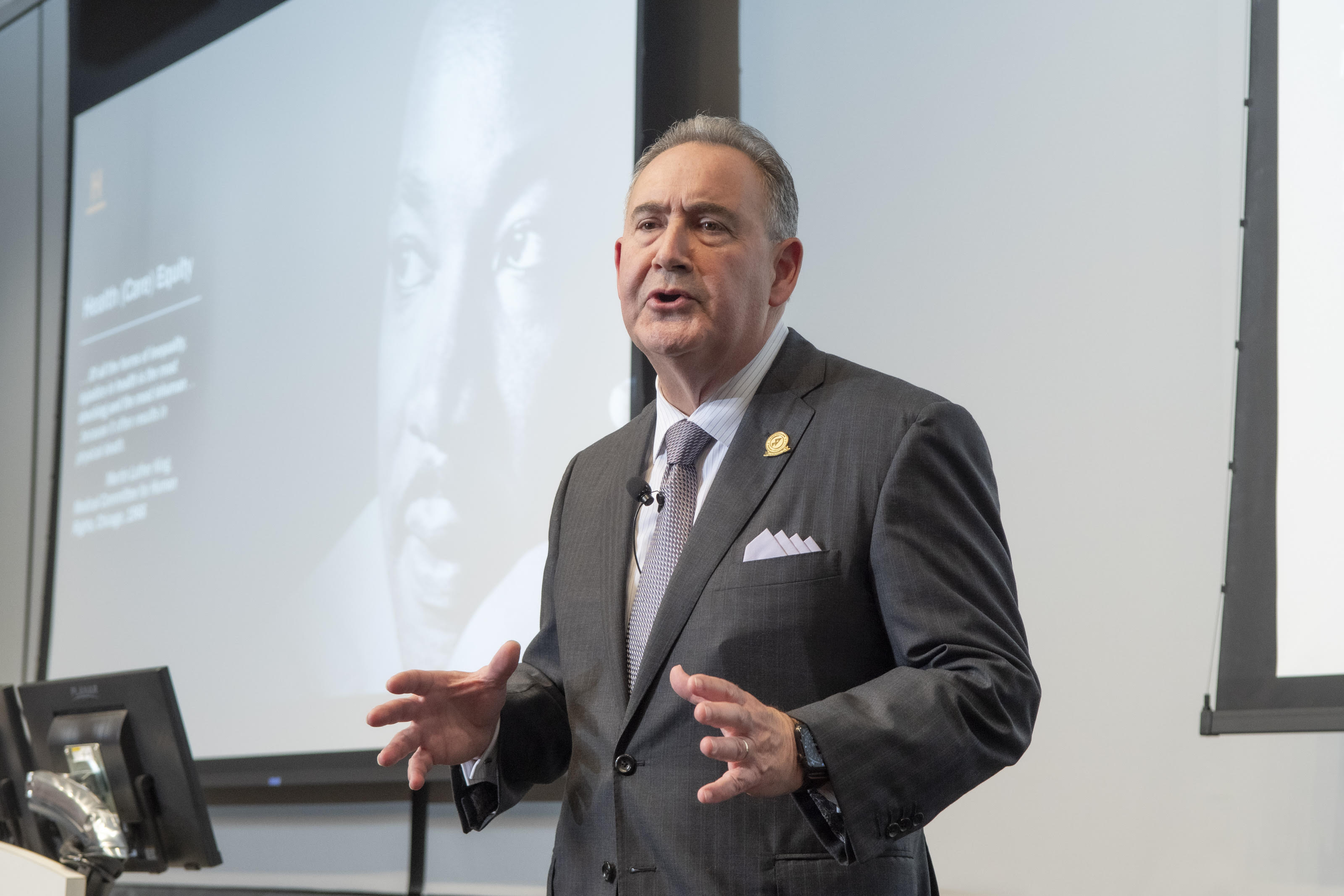

Jonathan Perlin (VCU Ph.D. ’91, MD ’92, and MSHA ’97 ), outlines accrediting organization’s four-point agenda with a focus on environmental sustainability, calling on VCU leaders to pull “levers” for change

By Jeff Kelley

Health equity. Environmental sustainability. Learning. Performance integration and improvement. Taken together, “H.E.L.P” is the agenda The Joint Commission enterprise accrediting organization is taking to address the myriad challenges facing healthcare organizations, its workforce, and patient care.

Taken together, “H.E.L.P” is the agenda The Joint Commission enterprise accrediting organization is taking to address the myriad challenges facing healthcare organizations, its workforce, and patient care.

That agenda was outlined to VCU Health Administration students by Jonathan Perlin, M.D., Ph.D., the Commission president and CEO and the 2023 Paul A. Gross Landmarks in Leadership Lecture series headliner. But over the course of the hour-long presentation, it was the “E” — Environmental sustainability — where the three-time VCU graduate invested the majority of the time.

“As an untoward side effect of intending to do good, as we wish to do in our communities, we're doing harm. Healthcare workers need [to] take the lead in actually remediating some of the adverse effects of what we're doing,” Perlin told the group of MHA and MSHA students, admitting that even when he started at the Joint Commission in March 2022 after top leadership roles with HCA Healthcare, he was unaware of the linkages between the industry and climate change.

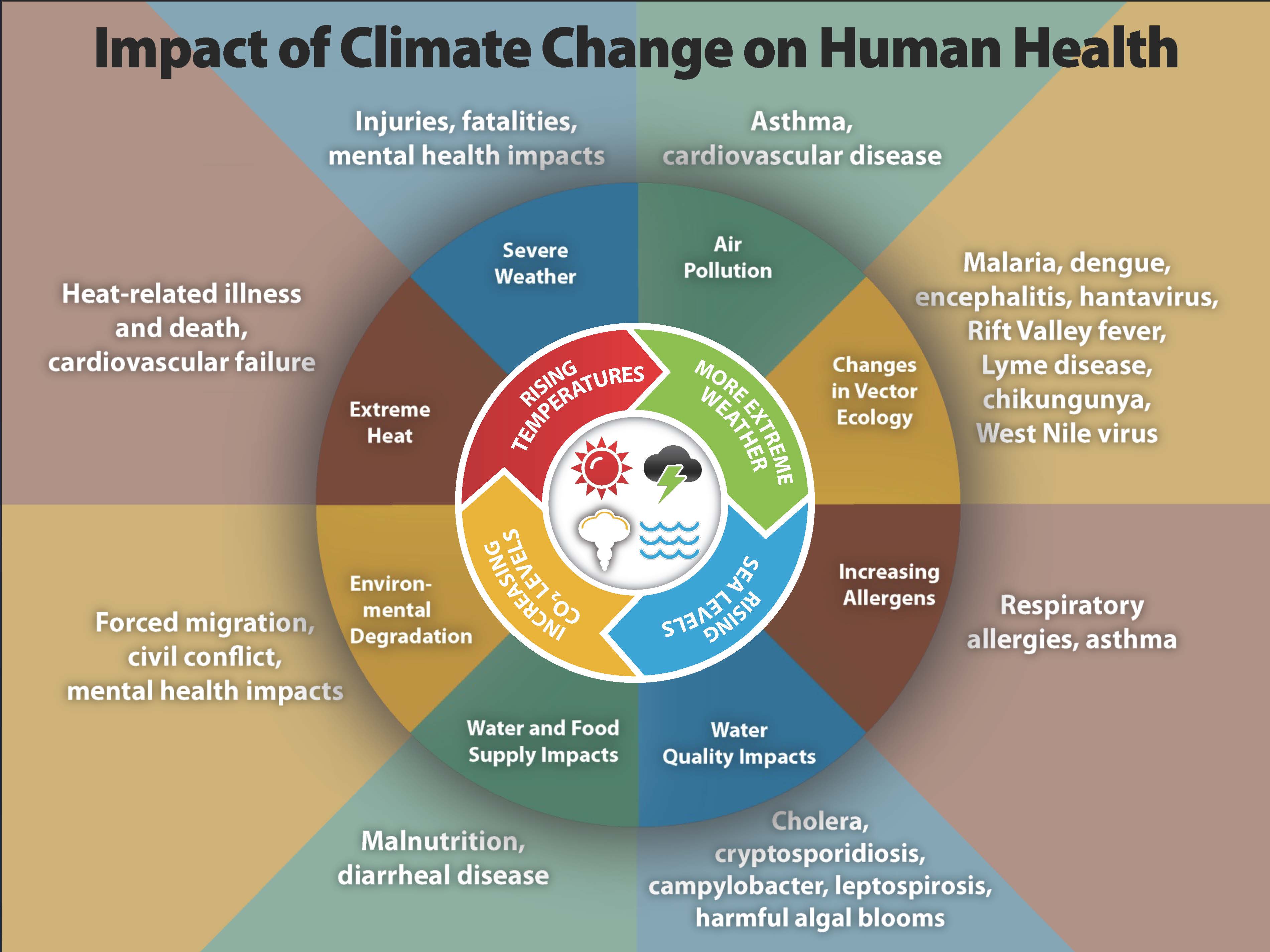

He laid out the case for how healthcare plays a large part: If “Healthcare” was a country, he explained, it would be the fifth highest-polluting nation — and the U.S. contributes to more than a quarter of that damage. And that harm also impacts patients in “an unvirtuous cycle,” he said, explaining how as temperatures and carbon dioxide levels rise, the effects ultimately exacerbate cardiac and respiratory diseases — especially in already vulnerable patient populations.

Those low-income, socioeconomically disadvantaged patients “can't buy their way out of the harms that are in their way,” he said. “Climate change, and our role in healthcare, is not only an environmental and social justice issue, it’s an issue of health equity and ultimately patient safety.”

Citing a statistic from Jeff Goodell’s New York Times nonfiction bestseller The Heat Will Kill You First, Perlin noted that in 2022, there were quarter-million deaths from firearms — yet almost double that number from heat. Over the next 48 years, the number of people living in “extreme heat zones” will rise from 30 million to 2 billion, the book notes. Urban environments are particularly at risk, as they feature reduced natural surfaces that trap heat. And cities are where the most vulnerable populations live.

There’s hope, because there are “levers” health administrators can pull to combat climate change at a system level, Perlin said. That includes three scopes: “the stuff we do, the stuff we burn, and the stuff we buy,” he said. “It’s really that simple to think about, because that gives us insight into what the levers are that we can pull to make change.”

- Scope 1: Stuff we do. Perlin honed in on the pollution created by anesthetics in operating rooms, and metered-dose inhalers for conditions such as asthma (one of the conditions impacted by climate change). Both trap volatile fluorocarbons that create disproportionately high climate impacts — estimated by one Yale University professor at 10% of total global warming. Kaiser Permanente, for example, lowered its gas flow rate for anesthesia and saved $20 million in one year, he said. Similarly, the University of Michigan's 80% reduction in nitrous oxide pumped through hospitals was equivalent to eliminating about 12 million driven miles, or 550,000 gallons of gas. Metered dose inhalers, powered by propellants, can also be replaced in many cases by dry powder inhalers, he said.

- Scope 2: Stuff we burn, turning his attention to fuel, power, and water consumption. Hospitals consume three times the energy of an average commercial building, he said. Health systems have “big opportunities” to conserve energy with more efficient HVAC systems, LED lighting, replacing windows, and other measures. “It saves money, and saves the environment,” he said.

- Scope 3: Stuff we buy and use. Perlin said there is an opportunity in hospitals to reduce medical waste — 15% of which is toxic — and substitute “consumables for reusables.” The average patient creates about 20 pounds of trash per day — one ton per day in a 100-bed hospital. Perlin showed how Cleveland Clinic’s waste-reduction strategies save more than $4 million a year. At Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Annandale, administrators saved nearly $200,000 in annual waste disposal fees through better segregation of trash and staff education. Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center diverted 297 tons of waste from landfills by using reusable isolation gowns.

Perlin also acknowledged Marlon Levy, M.D., interim senior vice president for health sciences at VCU and the interim CEO of the VCU Health System, was in the audience and “taking notes.”

As an accrediting organization whose approval is considered critical for Medicare and Medicaid participation, The Joint Commission is building new standards to ensure the health systems do not inadvertently contribute to excess consumption, and to accelerate industry efforts in decarbonization. Beyond savings, there are also financial incentives for organizations that lower their emissions, including tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act and other federal grants.

As an accrediting organization whose approval is considered critical for Medicare and Medicaid participation, The Joint Commission is building new standards to ensure the health systems do not inadvertently contribute to excess consumption, and to accelerate industry efforts in decarbonization. Beyond savings, there are also financial incentives for organizations that lower their emissions, including tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act and other federal grants.

“We changed our posture at The Joint Commission from just a moral stance to a very practical stance that's picking up speed," he said. “Caring for our community means mitigating the unintended harm. The evidence is increasingly inescapable. It's not just environmental and social justice — it's health equity and safety.”

And, he noted, that health administrators can pull such levers and turn back the climate-change clock “is what inspires me each and every day.”

Perlin’s focus on healthcare and climate change came a year and a half after Carrie Owen Plietz, FACHE, a 2000 VCU MHA graduate who serves as the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Regional President, made a similar plea to students in her May 2022 Gross lecture for more attention toward sustainability in healthcare.